Saturday, June 26, 2004

Book Review: The Private Eye in Hammett and Chandler by Robert B. Parker (1984)

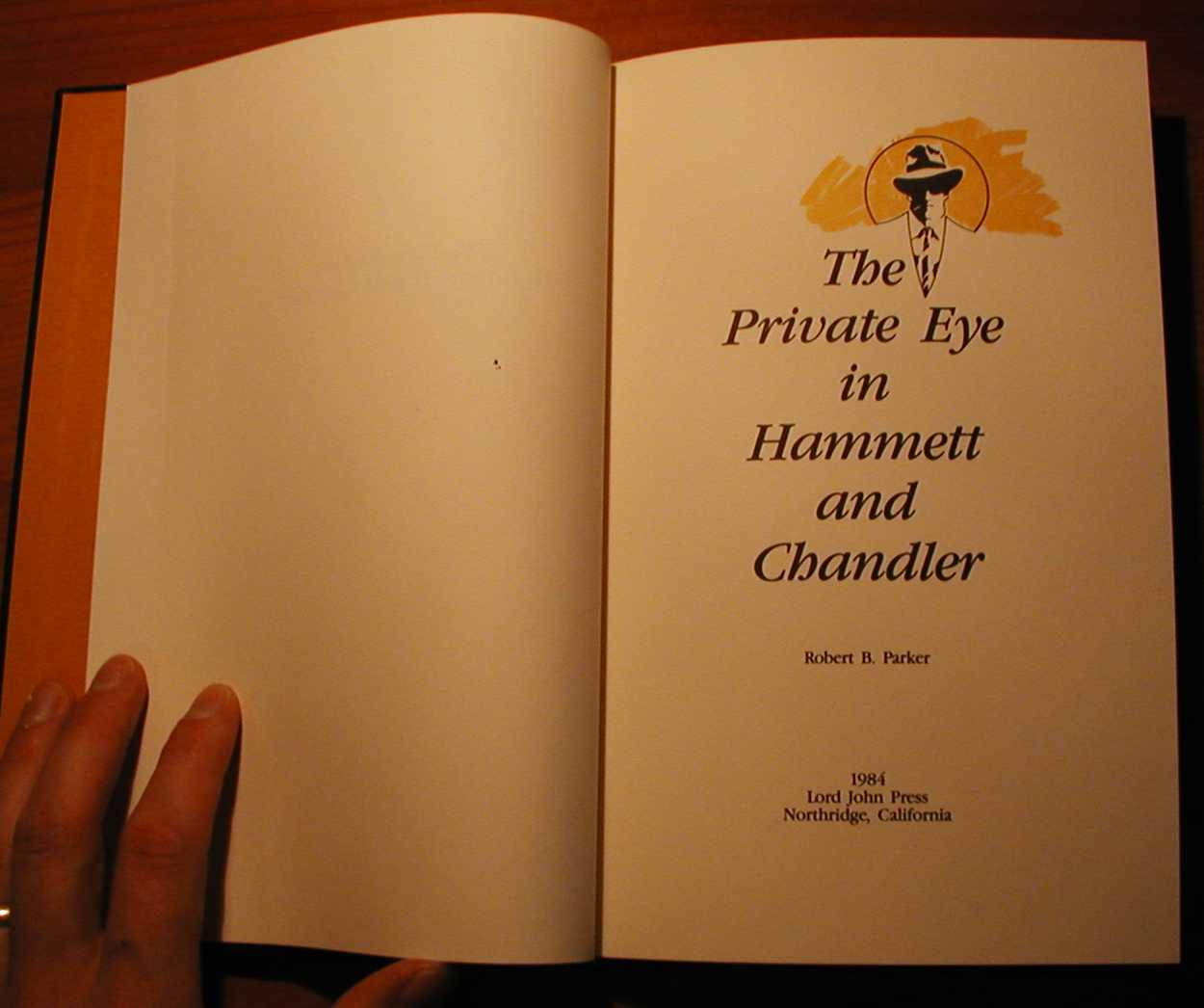

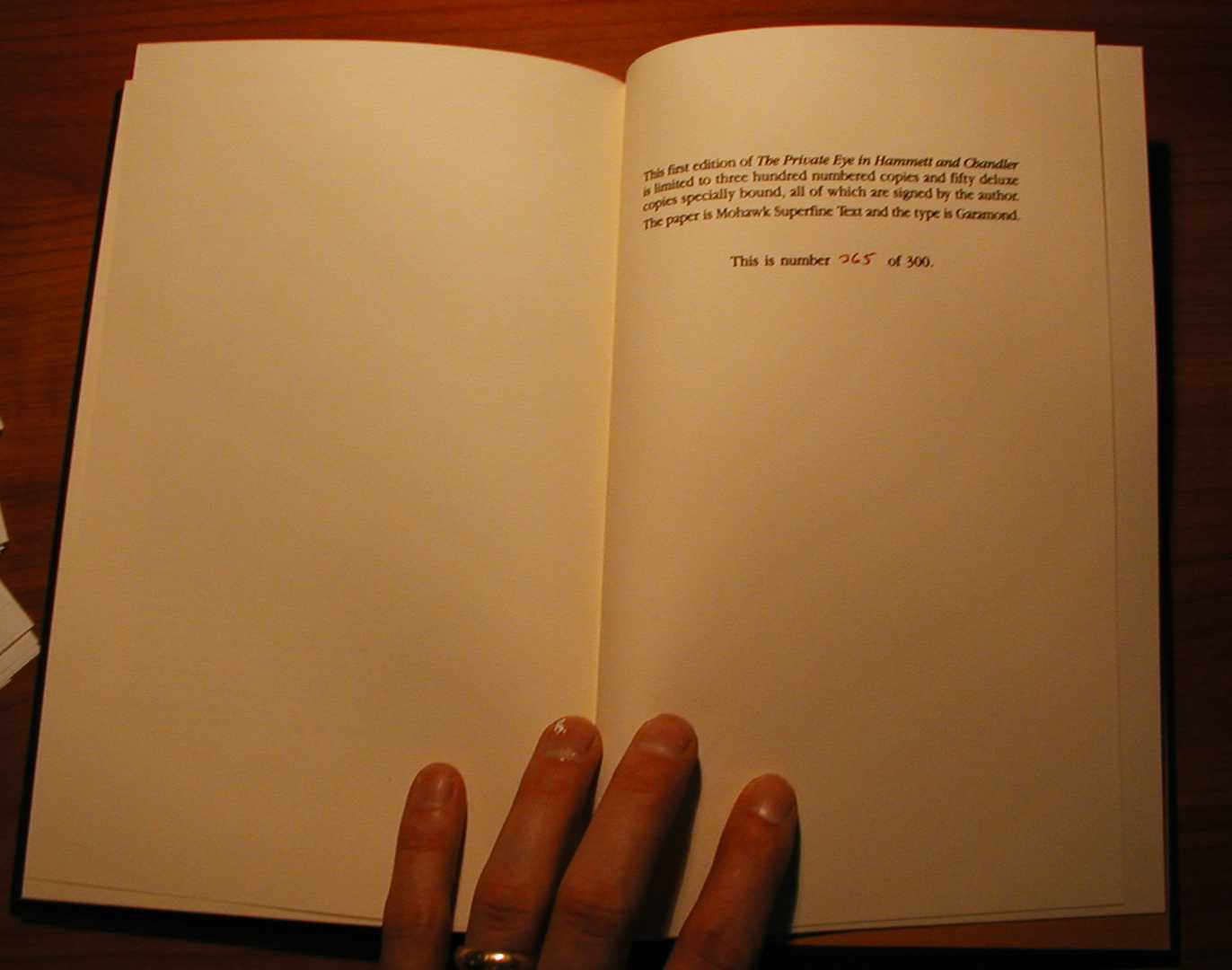

Well, finally I have saved enough money up from my, er, prudence with purchasing one dollar books to save up for a copy of The Private Eye in Hammett and Chandler by Robert B. Parker. He stripped some of the academic verbiage from the dissertation he wrote for his PhD and published it as a limited edition via Lord John's Press in the early eighties. How limited? This printing was limited to 300; I think the more exclusive run was under 100, so there are fewer than 400 copies of this book in print. And I got one. Nyah, nyah.

Here are some pix:

Click any photo for super size

I've read all of Parker's fiction, some of his profiles, and some of his nonfiction, but this represents the greatest divergance from his normal style I've seen. He stilted its prose to impress some review board, or whatever group determines whether a master becomes a doctor, so I realize I, consumer, am not the target audience. Still, it's more stilted than most nonfiction I read for fun, Make Room for TV notwithstanding.

To summarize, Parker takes us on a six chapter, 63 page exploration of the hard-boiled detective character embraced by Dash and Raymond, exploring how they fit into the literary canon of American heroes. The first two chapters run through obligatory quotations from other critics and academics, which rather drags but undoubtedly proved that Parker did his research. Then, Parker explores earlier manifestations of the American hero archetype that led to hard-boiled private eyes: the frontiersman, demonstrated in James Fenimore Cooper's Leatherstocking tales and Daniel Boone's legendary biography.

Parker doesn't build a revolutionary case, nor does he really reveal any blinding insight into the scholarship of the hard-boiled detective--although my reading is certainly limited, but I have read some (American Tough, and so on). The biggest insight is not in the text itself, but in its relationship to how Parker would craft the Spenser novels.

Using this document, one can see an earlier step in Parker's thought processes than The Godwulf Manuscript. For example, he notes that neither the Continental Op nor Philip Marlowe could really describe the code of honor to which they adhere. Spenser and Hawk, in Parker's novels, don't suffer, at great length, from this flaw.

So it's an interesting read if you strive to emulate Parker's success by imitation and ceaseless devotion, or if you like Spenser, I guess. Although there are no We'd be fools not to, there is one Wouldn't it be pretty to think so?--proving that this really is Parker, with the throwaway allusions that characterize not only his novels, his screenplays, but also, apparently, his most serious nonfiction. Thankfully.

P.S. Class, why is it that two of the vendors selling this on Amazon.com are both selling the exact same copy, # 245, of this numbered limited edition? Never mind, class; I am cynical enough to guess.

To say Noggle, one first must be able to say the "Nah."

"I will."

Heather L. Igert,

angelweave.mu.nu

"Genuis."

Neil Steinberg,

Chicago Sun-Times

"Some wanker."

Kim du Toit,

on the Noggle Library.

"Brian J. Noggle apparently forgot that the proper design for a tin foil beanie calls for the shiny side out."

Robb Allen,

Sharp as a Marble.

"I'm weeping openly right now. Thanks for hurting my feelings, pinhead."

Bob Rybarcyzk,

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Visualize World Hegemony

Cog in the Machine

Tao Sharks

Humor not displayed

Beware of Conservative

3/30/03 - 4/6/03

4/6/03 - 4/13/03

4/13/03 - 4/20/03

4/20/03 - 4/27/03

4/27/03 - 5/4/03

5/4/03 - 5/11/03

5/11/03 - 5/18/03

5/18/03 - 5/25/03

5/25/03 - 6/1/03

6/1/03 - 6/8/03

6/8/03 - 6/15/03

6/15/03 - 6/22/03

6/22/03 - 6/29/03

6/29/03 - 7/6/03

7/6/03 - 7/13/03

7/13/03 - 7/20/03

7/20/03 - 7/27/03

7/27/03 - 8/3/03

8/3/03 - 8/10/03

8/10/03 - 8/17/03

8/17/03 - 8/24/03

8/24/03 - 8/31/03

8/31/03 - 9/7/03

9/7/03 - 9/14/03

9/14/03 - 9/21/03

9/21/03 - 9/28/03

9/28/03 - 10/5/03

10/5/03 - 10/12/03

10/12/03 - 10/19/03

10/19/03 - 10/26/03

10/26/03 - 11/2/03

11/2/03 - 11/9/03

11/9/03 - 11/16/03

11/16/03 - 11/23/03

11/23/03 - 11/30/03

11/30/03 - 12/7/03

12/7/03 - 12/14/03

12/14/03 - 12/21/03

12/21/03 - 12/28/03

12/28/03 - 1/4/04

1/4/04 - 1/11/04

1/11/04 - 1/18/04

1/18/04 - 1/25/04

1/25/04 - 2/1/04

2/1/04 - 2/8/04

2/8/04 - 2/15/04

2/15/04 - 2/22/04

2/22/04 - 2/29/04

2/29/04 - 3/7/04

3/7/04 - 3/14/04

3/14/04 - 3/21/04

3/21/04 - 3/28/04

3/28/04 - 4/4/04

4/4/04 - 4/11/04

4/11/04 - 4/18/04

4/18/04 - 4/25/04

4/25/04 - 5/2/04

5/2/04 - 5/9/04

5/9/04 - 5/16/04

5/16/04 - 5/23/04

5/23/04 - 5/30/04

5/30/04 - 6/6/04

6/6/04 - 6/13/04

6/13/04 - 6/20/04

6/20/04 - 6/27/04

6/27/04 - 7/4/04

7/4/04 - 7/11/04

7/11/04 - 7/18/04

7/18/04 - 7/25/04

7/25/04 - 8/1/04

8/1/04 - 8/8/04

8/8/04 - 8/15/04

8/15/04 - 8/22/04

8/22/04 - 8/29/04

8/29/04 - 9/5/04

9/5/04 - 9/12/04

9/12/04 - 9/19/04

9/19/04 - 9/26/04

9/26/04 - 10/3/04

10/3/04 - 10/10/04

10/10/04 - 10/17/04

10/17/04 - 10/24/04

10/24/04 - 10/31/04

10/31/04 - 11/7/04

11/7/04 - 11/14/04

11/14/04 - 11/21/04

11/21/04 - 11/28/04

11/28/04 - 12/5/04

12/5/04 - 12/12/04

12/12/04 - 12/19/04

12/19/04 - 12/26/04

12/26/04 - 1/2/05

1/2/05 - 1/9/05

1/9/05 - 1/16/05

1/16/05 - 1/23/05

1/23/05 - 1/30/05

1/30/05 - 2/6/05

2/6/05 - 2/13/05

2/13/05 - 2/20/05

2/20/05 - 2/27/05

2/27/05 - 3/6/05

3/6/05 - 3/13/05

3/13/05 - 3/20/05

3/20/05 - 3/27/05

3/27/05 - 4/3/05

4/3/05 - 4/10/05

4/10/05 - 4/17/05

4/17/05 - 4/24/05

4/24/05 - 5/1/05

5/1/05 - 5/8/05

5/8/05 - 5/15/05

5/15/05 - 5/22/05

5/22/05 - 5/29/05

5/29/05 - 6/5/05

6/5/05 - 6/12/05

6/12/05 - 6/19/05

6/19/05 - 6/26/05

6/26/05 - 7/3/05

7/3/05 - 7/10/05

7/10/05 - 7/17/05

7/17/05 - 7/24/05

7/24/05 - 7/31/05

7/31/05 - 8/7/05

8/7/05 - 8/14/05

8/14/05 - 8/21/05

8/21/05 - 8/28/05

8/28/05 - 9/4/05

9/4/05 - 9/11/05

9/11/05 - 9/18/05

9/18/05 - 9/25/05

9/25/05 - 10/2/05

10/2/05 - 10/9/05

10/9/05 - 10/16/05

10/16/05 - 10/23/05

10/23/05 - 10/30/05

10/30/05 - 11/6/05

11/6/05 - 11/13/05

11/13/05 - 11/20/05

11/20/05 - 11/27/05

11/27/05 - 12/4/05

12/4/05 - 12/11/05

12/11/05 - 12/18/05

12/18/05 - 12/25/05

12/25/05 - 1/1/06

1/1/06 - 1/8/06

1/8/06 - 1/15/06

1/15/06 - 1/22/06

1/22/06 - 1/29/06

1/29/06 - 2/5/06

2/5/06 - 2/12/06

2/12/06 - 2/19/06

2/19/06 - 2/26/06

2/26/06 - 3/5/06

3/5/06 - 3/12/06

3/12/06 - 3/19/06

3/19/06 - 3/26/06

3/26/06 - 4/2/06

4/9/06 - 4/16/06

4/16/06 - 4/23/06

4/23/06 - 4/30/06

4/30/06 - 5/7/06

5/7/06 - 5/14/06

5/14/06 - 5/21/06

5/21/06 - 5/28/06

5/28/06 - 6/4/06

6/4/06 - 6/11/06

6/11/06 - 6/18/06

6/18/06 - 6/25/06

6/25/06 - 7/2/06

7/2/06 - 7/9/06

7/9/06 - 7/16/06

7/16/06 - 7/23/06

7/23/06 - 7/30/06

7/30/06 - 8/6/06

8/6/06 - 8/13/06

8/13/06 - 8/20/06

8/20/06 - 8/27/06

8/27/06 - 9/3/06

9/3/06 - 9/10/06

9/10/06 - 9/17/06

9/17/06 - 9/24/06

9/24/06 - 10/1/06

10/1/06 - 10/8/06

10/8/06 - 10/15/06

10/15/06 - 10/22/06

10/22/06 - 10/29/06

10/29/06 - 11/5/06

11/5/06 - 11/12/06

11/12/06 - 11/19/06

11/19/06 - 11/26/06

11/26/06 - 12/3/06

12/3/06 - 12/10/06

12/10/06 - 12/17/06

12/17/06 - 12/24/06

12/24/06 - 12/31/06

12/31/06 - 1/7/07

1/7/07 - 1/14/07

1/14/07 - 1/21/07

1/21/07 - 1/28/07

1/28/07 - 2/4/07

2/4/07 - 2/11/07

2/11/07 - 2/18/07

2/18/07 - 2/25/07

2/25/07 - 3/4/07

3/4/07 - 3/11/07

3/11/07 - 3/18/07

3/18/07 - 3/25/07

3/25/07 - 4/1/07

4/1/07 - 4/8/07

4/8/07 - 4/15/07

4/15/07 - 4/22/07

4/22/07 - 4/29/07

4/29/07 - 5/6/07

5/6/07 - 5/13/07

5/13/07 - 5/20/07

5/20/07 - 5/27/07

5/27/07 - 6/3/07

6/3/07 - 6/10/07

6/10/07 - 6/17/07

6/17/07 - 6/24/07

6/24/07 - 7/1/07

7/1/07 - 7/8/07

7/8/07 - 7/15/07

7/15/07 - 7/22/07

7/22/07 - 7/29/07

7/29/07 - 8/5/07

8/5/07 - 8/12/07

8/12/07 - 8/19/07

8/19/07 - 8/26/07

8/26/07 - 9/2/07

9/2/07 - 9/9/07

9/9/07 - 9/16/07

9/16/07 - 9/23/07

9/23/07 - 9/30/07

9/30/07 - 10/7/07

10/7/07 - 10/14/07

10/14/07 - 10/21/07

10/21/07 - 10/28/07

10/28/07 - 11/4/07

11/4/07 - 11/11/07

11/11/07 - 11/18/07

11/18/07 - 11/25/07

11/25/07 - 12/2/07

12/2/07 - 12/9/07

12/9/07 - 12/16/07

12/16/07 - 12/23/07

12/23/07 - 12/30/07

12/30/07 - 1/6/08

1/6/08 - 1/13/08

1/13/08 - 1/20/08

1/20/08 - 1/27/08

1/27/08 - 2/3/08

2/3/08 - 2/10/08

2/10/08 - 2/17/08

2/17/08 - 2/24/08

2/24/08 - 3/2/08

3/2/08 - 3/9/08

3/9/08 - 3/16/08

3/16/08 - 3/23/08

3/23/08 - 3/30/08

3/30/08 - 4/6/08

4/6/08 - 4/13/08

4/13/08 - 4/20/08

4/20/08 - 4/27/08

4/27/08 - 5/4/08

5/4/08 - 5/11/08

5/11/08 - 5/18/08

5/18/08 - 5/25/08

5/25/08 - 6/1/08

6/1/08 - 6/8/08

6/8/08 - 6/15/08

6/15/08 - 6/22/08

6/22/08 - 6/29/08

6/29/08 - 7/6/08

7/6/08 - 7/13/08

7/13/08 - 7/20/08

7/20/08 - 7/27/08

7/27/08 - 8/3/08

8/3/08 - 8/10/08

8/10/08 - 8/17/08

8/17/08 - 8/24/08

8/24/08 - 8/31/08

8/31/08 - 9/7/08

9/7/08 - 9/14/08

9/14/08 - 9/21/08

9/21/08 - 9/28/08

9/28/08 - 10/5/08

10/5/08 - 10/12/08

10/12/08 - 10/19/08

10/19/08 - 10/26/08

10/26/08 - 11/2/08

11/2/08 - 11/9/08

11/9/08 - 11/16/08

11/16/08 - 11/23/08

11/23/08 - 11/30/08

11/30/08 - 12/7/08

12/7/08 - 12/14/08

12/14/08 - 12/21/08

12/21/08 - 12/28/08

1/25/09 - 2/1/09

2/1/09 - 2/8/09

2/8/09 - 2/15/09

2/15/09 - 2/22/09

2/22/09 - 3/1/09

3/1/09 - 3/8/09

3/8/09 - 3/15/09

3/15/09 - 3/22/09

3/22/09 - 3/29/09

3/29/09 - 4/5/09

4/5/09 - 4/12/09

4/12/09 - 4/19/09

4/19/09 - 4/26/09

4/26/09 - 5/3/09

5/3/09 - 5/10/09

5/10/09 - 5/17/09

5/17/09 - 5/24/09

5/24/09 - 5/31/09

5/31/09 - 6/7/09

6/7/09 - 6/14/09

6/14/09 - 6/21/09

6/21/09 - 6/28/09

6/28/09 - 7/5/09

7/5/09 - 7/12/09

7/12/09 - 7/19/09

7/19/09 - 7/26/09

7/26/09 - 8/2/09

8/2/09 - 8/9/09

8/9/09 - 8/16/09

8/16/09 - 8/23/09

8/23/09 - 8/30/09

8/30/09 - 9/6/09

9/6/09 - 9/13/09

9/13/09 - 9/20/09

9/20/09 - 9/27/09

9/27/09 - 10/4/09

10/4/09 - 10/11/09

10/11/09 - 10/18/09

10/18/09 - 10/25/09

10/25/09 - 11/1/09

11/1/09 - 11/8/09

11/8/09 - 11/15/09

11/15/09 - 11/22/09

11/22/09 - 11/29/09

11/29/09 - 12/6/09

12/6/09 - 12/13/09

12/13/09 - 12/20/09

12/20/09 - 12/27/09

12/27/09 - 1/3/10

1/3/10 - 1/10/10